As we head towards the end of February, we continue to celebrate Black History Month by honoring African American achievements, contributions, and struggles throughout history. Within the Ursinus community, students and faculty alike have celebrated this month, bringing to campus the importance surrounding the month-long observance. Here, some of our own professors reflect on the question, “What does Black History mean to me?”

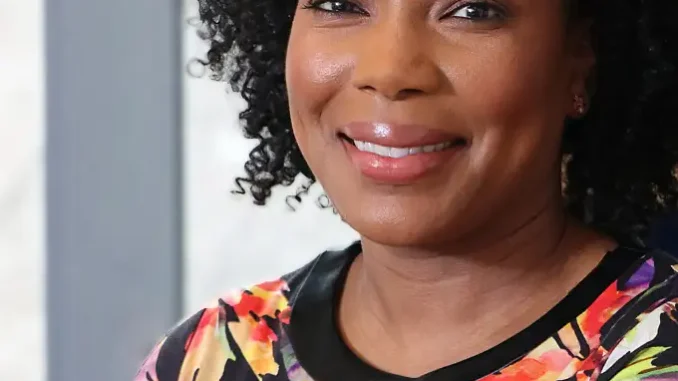

Dr. Patricia Lott, Associate Professor of American Studies, African American and Africana Studies, and English:

“For me, Black History Month is a specially designated time for reflecting on, celebrating, and recommitting myself to the work that I do the other eleven months of the year as a student and a scholar of Black Studies. That work is studying the arts, cultures, histories, ingenuities, intellectual traditions, political philosophies, and social movements of African and African-descended peoples as we continue to struggle against incomplete emancipation and unfinished abolition as well as strive for self-determination and liberation. It is a time for honoring the ancestors whose lives, labors, and love paved the path for this striving, ancestors like the founding father of Black History Month, Dr. Carter G. Woodson; abolitionist activists Harriet Tubman, David Walker, and Henry Highland Garnet; antilynching crusader Ida B. Wells-Barnett; civil rights giants Fannie Lou Hamer and Martin Luther King, Jr.; Black Nationalist, Pan-Africanist, and ideological father of Black Studies Malcolm X; creatives Phyllis Wheatley—a founding mother of the African American literary tradition—Charles Chesnutt, James Baldwin, and Toni Morrison; and many, many more path-paving predecessors, sung and unsung alike. It is a time for taking stock of our present conditions through the hindsight offered by hard-learned past lessons and the foresight offered by keen-eyed Black prophetic traditions. It is a time for pondering questions posed to us by said prophets and by many Afrofuturists, including: how can we envision and make liberationist futures from our unsettling present and unfinished pasts?”

Dr. Edward Onaci, Associate Professor of History and African American & Africana Studies:

As a member of the Association for the Study of African American and History, Dr. Onaci shared some statements from the organization in which his ideas aligned:

“As part of the global African diaspora, people of African descent in the United States have viewed their role in history as critical to their own development and that of the world. Along with writing Black histories, antebellum Black scholars north of slavery started observing the milestones in the struggle of people of African descent to gain their freedom and equality. Revealing their connection to the diaspora, they commemorated the Haitian Revolution, the end of the slave trade, and the end of slavery in Jamaica. They observed American emancipation with Watch Night, Jubilee Day, and Juneteenth celebrations. Eventually they feted the lives of individuals who fought against slavery, most notably Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. The scholar Arthur A. Schomburg captured the motivation of Black people to dig up their own history and present it to the world: ‘The American Negro must remake his past in order to make his future.’”

“To understand the modern world, especially nations where Black peoples form a significant population, one must grapple with the impact that the public observances have had on the past and the present. This year, when we are also commemorating the 250th anniversary of United States independence, it is important to tell not only an inclusive history, but an accurate one. We have never had more need to examine the role of Black History Month than we do when forces weary of democracy seek to use legislative means and book bans to excise Black history from America’s schools and public culture. Black history’s value is not its contribution to mainstream historical narratives, but its resonance in the lives of Black people.”